Got the travel bug? Sometimes the rarest dolphins in Hawai‘i seem to get it too. Satellite tags are giving researchers an exclusive look at Hawaiian false killer whale movement and habitat use. And their movements are occasionally off the charts—or at least all over them.

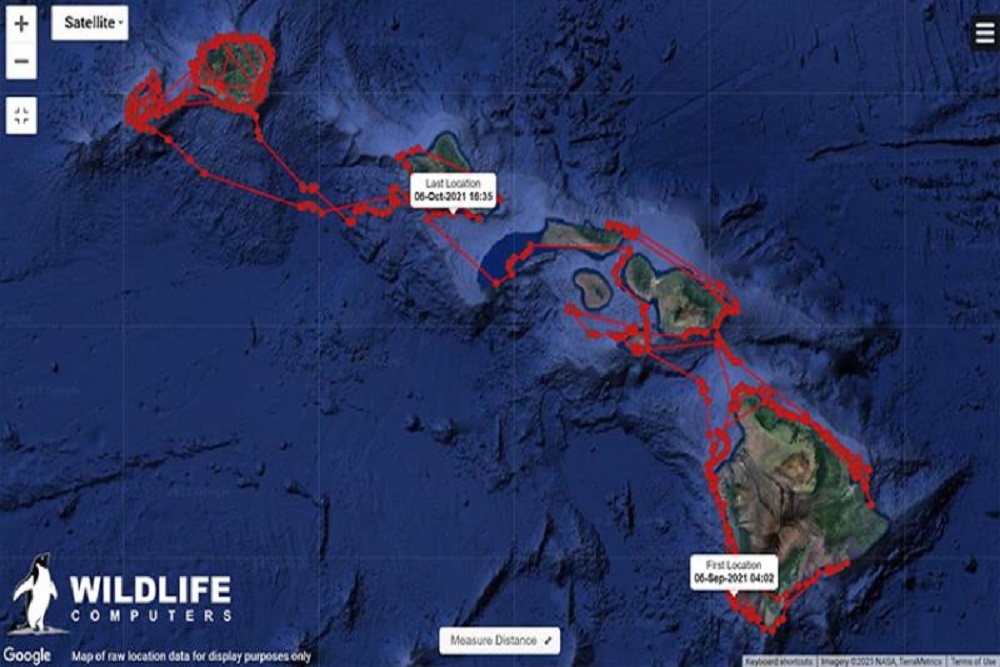

Last year, Cascadia Research Collective (CRC), a NOAA Fisheries species recovery grant partner, deployed a satellite tag on a false killer whale, identified as HIPc808. The whale is from the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular population. After tagging HIPc808 in waters off south Kona (north of Miloli‘i), the team logged the animal’s 10-day jaunt up the chain to Ni‘ihau. It made a few loops around specific islands along the way.

Since February 2000, NOAA Fisheries and CRC have partnered to study whales and dolphins in Hawai‘i, focusing on less well-studied species. The CRC team, led by Dr. Robin W. Baird, is constantly working to better understand the lives of false killer whales. They study their population size, social structure, and individual movement patterns, among other things.

This information is critical not only to understanding threats to false killer whales, like fisheries interactions, but also in developing management strategies to minimize those threats.

What Tags Tell Us

HIPc808 is part of the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular population of false killer whales, one of three populations of false killer whales in Hawai‘i. Successfully tagging an individual from this group provides important data to better understand this population and to help inform NOAA Fisheries’ recovery efforts.

Years of tagging data are revealing how false killer whales are using their habitat around the main Hawaiian Islands. According to Baird, their overall movement rates are faster than any of the other species the team has satellite tagged. Individuals move quite rapidly among islands. HIPc808’s 10-day journey gave the CRC team and their social media followers a formidable example of false killer whales’ speedy island-hopping.

Through aggregated satellite data, CRC has identified three high-use areas for the main Hawaiian Islands insular population:

- North of Moloka‘i and Maui

- Southwest Lāna‘i

- Northern end of Hawai‘i Island

The data have also revealed that while on windward sides of islands, false killer whales spend time in more concentrated areas closer to shore. On leeward sides, they tend to spread out over larger areas.

Baird said the CRC team is still looking to learn more. “We’re trying to increase our understanding of seasonal and cluster-specific spatial use,” he said. By better understanding where and how the animals use their habitat, NOAA can better inform fishermen about avoiding these high-use areas. This will minimize the chances of interacting with false killer whales.

False killer whales in the main Hawaiian Islands are known to occur in distinct social “clusters.” These long-term groups made up of closely related animals, akin to the pods of the more famous orca. Better understanding the spatial distribution of each cluster is important to preserving what is already a small population.

“The bonds and cultural knowledge within these clusters are fundamental to false killer whale survival,” said Krista Graham, NOAA Fisheries recovery coordinator for the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale. “Understanding ‘social connectedness’ is a key component of our recovery efforts.”

The recovery plan for the main Hawaiian Island insular false killer whale, released in 2021, outlines the path and tasks required to restore and secure self-sustaining wild populations. The goal is to safeguard the species’ future so that they no longer need protection under the Endangered Species Act.

False Killer Whale Following

New insights on false killer whales are not just getting NOAA Fisheries and the CRC team excited. The team shares about their encounters with Hawai‘i whales and dolphins, including false killer whales, with regular updates from the field. They even have a fan following on Facebook (@CascadiaResearch).

“A lot of what we are trying to do is build a constituency that wants to support conservation of [false killer whales] and other species,” said Baird, “So part of it is just letting people know they exist, giving them a connection in near real time to where the animals are.”

Understanding the rarest dolphin in Hawai‘i waters won’t be a 10-day sprint like HIPc808’s recent trip. But long-term tracking and partnerships are beginning to demystify this elusive local resident—and giving us a firsthand travelogue of a species on the brink.