AS DELIVERED

DR. ANTHONY WUTOH: Good evening. I’m Dr. Anthony Wutoh, and I currently serve as the provost and chief academic officer at Howard University. It is my honor and my pleasure to welcome you to the Gwendolyn and Colbert King Endowed Chair in Public Policy Lecture Series. And before I turn this event over to our chair, Ms. Donna Brazile, I wanted to take this point of personal privilege to thank her for the exemplary role that she has played as the longest-serving King chair in this series.

We’re reminded, as I was entering into the building, that this is the fourth year that Ms. Brazile has served as the King chair, and if you think about the events that have taken place both in this country and around the world over the last four years – things we couldn’t have anticipated, things we couldn’t have prepared for: a monumental presidential election; the election of the first African American woman and Howard alum to serve as Vice President, VP Kamala Harris; a global pandemic; a crisis in Europe – all of these things we could not have predicted, and Ms. Brazile has handled them wonderfully in chairing this lecture series and providing the opportunity for our students to be engaged in national and international affairs.

Please join me in extending our thanks and appreciation to Ms. Donna Brazile.

MS. DONNA BRAZILE: Thank you, sir.

DR. WUTOH: Donna, I’ll turn things over to you now.

MS. BRAZILE: Thank you so much. And thank you, Provost Wutoh, for your amazing and tremendous support of the King Lecture Series.

The King Lecture Series brings students, faculty, administrators, the Howard Alumni Association, and guest speakers together to exchange ideas and explore our common interests on some of the most important public policy issues facing our nation here and abroad. For over 14 years, this program has provided students with access to a wide variety of leading scholars, public policy advocates, and high-level government officials, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, House Majority Whip James Clyburn, Michael Steele, the former chair of the Republican National Committee, and most recently Secretary Marcia Fudge of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Kristen Clarke, Assistant U.S. Attorney General for Civil Rights.

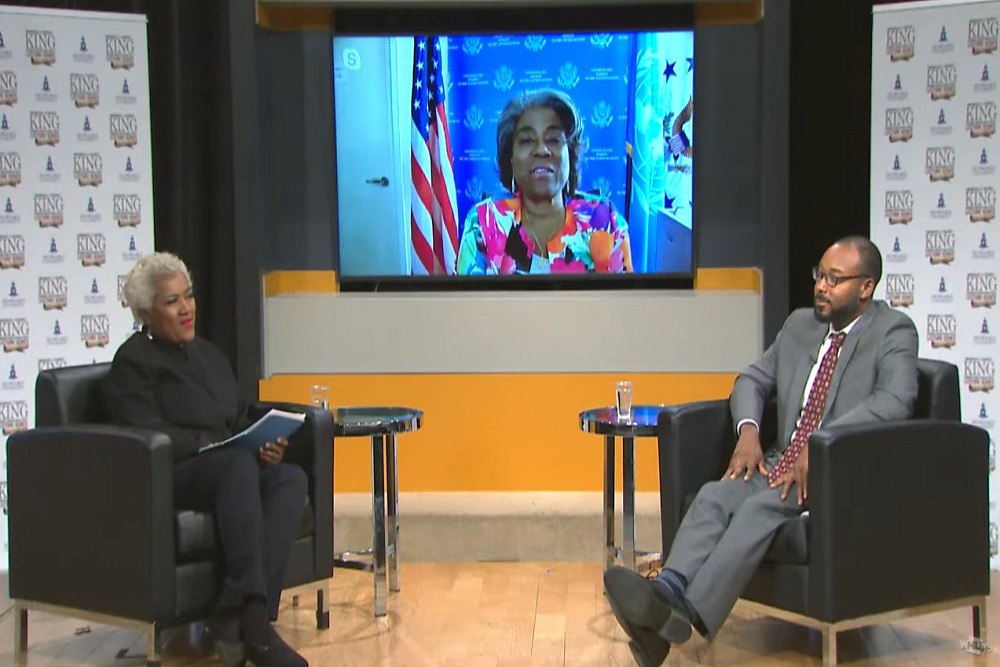

This semester, our them is “Make the Future Your Own: Building Stronger Together.” For our final program, we are honored to have as our special guest the Honorable Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield and Professor Justin Hansford.

Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield was nominated by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., to be the Representative of the United States of America to the United Nations as well as the Representative of the United States of America in the Security Council of the United Nations on January 20th, 2021. She is a career diplomat who returned to public service after retiring from a 35-year distinguished career with the U.S. Foreign Service in 2017. From 2013 to 2017, she served as the assistant secretary of state for African affairs, where she led the bureau focused on the development and management of the U.S. policy towards sub-Saharan Africa. Prior to this appointment, she served as director general of the Foreign Service and director of human resources from 2012 to 2013, leading a team in charge of the State Department’s 70,000-strong workforce.

Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield’s distinguished Foreign Service career includes an ambassadorship to Liberia from 2008 to 2012 and postings in Switzerland and the United States Mission to the United Nations in Geneva, Pakistan, Kenya, the Gambia, Nigeria, and Jamaica. In Washington, D.C., she served as the principal deputy assistant secretary of the Bureau of African Affairs from 2006 to 2008, and as deputy assistant secretary of the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration from 2004 to 2006.

Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield was the 2017 recipient of the University of Minnesota Hubert Humphrey Public Leadership Award; the 2015 recipient of the Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Service Award; and the 2000 recipient of the Warren Christopher Award for Outstanding Achievement in Global Affairs. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Louisiana State University, my alma mater, as well, and a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin, where she did work toward a doctorate. She received an honorary doctor of law degree from the University of Wisconsin in May of 2018 and an honorary doctor of philosophy from the University of Liberia in May of 2012.

Let me also welcome back to the King Lecture Series Professor Justin Hansford, who is a leading scholar activist in the fields of racial justice, human rights, and law and social movement. He is the founder and executive director of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center and a law professor at Howard University’s School of Law. Professor Hansford was recently nominated and elected to serve on the newly created and historic United Nations Permanent Forum for the People of African Descent, a global space for all people of African descent to come together to build a better world.

Upon his election, Professor Hansford said, and I quote, “It’s an honor to receive this nomination from the Ambassador. If confirmed, I hope to involve the entire Howard University campus – students, staff, faculty – in this project establishing this new forum as a resource and a platform for people of African descent around the world to fight for their human rights,” end of quote. So I want to also add to this, the forum will help create a better world for Black people everywhere.

Professor Hansford previously served as a democracy project fellow at Harvard University, a visiting professor of law at Georgetown University, and an associate professor of law at St. Louis University. His scholarship has appeared in academic journals and various universities, including Harvard, Georgetown, Fordham, and the University of California at Hastings. Professor Hansford is also a member of the Stanford Medicine Commission on Justice and Equity. Professor Hansford holds a bachelor of arts from Howard University and a JD from Georgetown University. He also earned a Fulbright Scholar award to study the legal career of Nelson Mandela and served as a clerk for Judge Damon Keith of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

Welcome, Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield, and congratulations to you, Professor Hansford, and thank you for bringing this program here to Howard University. We are so excited about the forum, and I cannot wait to find out more about it. Let’s also welcome our viewing audiences both in the studio and via the WHUT YouTube page. For those of you viewing online, please send your comments or questions to #KingLectureSeries.

So let’s get started. Madam Ambassador, let’s start with your incredible journey. What led you to a career in the Foreign Service, and why did you come out of retirement to take this role in the United Nations at such a time as this?

AMBASSADOR LINDA THOMAS-GREENFIELD: Thank you so much, and I can’t tell you how happy I am to be here with both of you.

As you noted, I’m from Louisiana, and Louisiana is pretty distant from the diplomatic world. So it was not an area that I grew up knowing much about. But I had the fortunate experience when I was in eighth grade, going to a segregated school, living in a segregated community in a small town in – outside of Baton Rouge, that Peace Corps sent Peace Corps volunteers who were training to go to Somalia and Swaziland to our community. There was an HBCU there that had closed down: Leland College. And they used the facilities of Leland College to train the volunteers. And they brought African teachers from Swaziland and from Somalia to teach the volunteers the language, and they invited the little kids from the community, and I was a little kid – I was in eighth grade – to come over after school to engage with the volunteers and to learn a little bit about the languages they were teaching the volunteers.

And so I took Siswati. I can’t say I remember a word, but it really whetted my appetite for international affairs. It raised my interest in knowing a little bit about Africa. And I moved on and graduated from high school, went to LSU. I intended to be a lawyer, Professor. That had been my intention, but sometimes doors are opened for you that you don’t expect. And I had a professor that encouraged me to go to the University of Wisconsin to study, and I went there with the idea that I was going to spend a year, get a one-year master’s degree in public administration and come back to go to law school.

But lo and behold, I would meet one of those African teachers, a woman by the name of Glory Mamba (ph), at the University of Wisconsin, and I remembered her and became more and more interested in Africa, and then got accepted into the University of Wisconsin’s PhD program to study African Studies. I would go to Liberia in the 1970s, probably before most of the students – and I know before most of the students in the audience were born, but maybe Professor Hansford, it could even be before you were born – but I went to Liberia in 1978 and I can tell you the rest is history. And so, I spent 35 years in the Foreign Service, and I loved every moment of it.

I retired in 2017, and I looked forward to my retirement. But when I was asked by the President if I would be interested in working in his administration, I said yes without even knowing what he wanted me to do. And I have to say I was shocked when I learned that it was to accept this position here in New York as the U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations. And I have been here just over a year; I have not regretted that decision one moment. I came to serve. I came to serve the American people. I came to reassert American leadership in the multilateral space. And I think while the work is still ongoing that we’ve had tremendous success, including our work in getting Professor Hansford elected to his position.

MS. BRAZILE: Before I ask Professor Hansford about his journey, let me ask you: Have you been back to Liberia? Have you stayed in touch with many of the nations that you have come to travel and serve in the capacity as our ambassador?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: I have. I have definitely stayed in touch with Liberia. I haven’t traveled there. I – my last trip to Liberia was in March of 2020, just as COVID started, but I had an opportunity to engage with Liberians there. I have gone to Africa. I traveled to Mali and Niger and as well as to Gabon since I’ve been in this position, and I stay engaged on Africa issues here. I like to say to people I’m not the permanent representative for African affairs. I cover the globe. But there are 54 countries on the continent of Africa, so Africa cannot be ignored anywhere. It can’t be ignored here at the United Nations and it can’t be ignored in our bilateral relationships. The countries there are so important to what we want to achieve in our relationships with African countries, but also in our global goals as well. So I am engaged very, very extensively with African colleagues here.

MS. BRAZILE: Thank you so much. I’m going to ask Justin about his path from Howard’s campus to the international stage, reflecting on his time as a Fulbright scholar studying the life of Nelson Mandela. So what led you to pursue this career path?

MR. HANSFORD: Well, my path was an uneven path. I was born here in Washington, D.C. I grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland. Had an up-and-down high school career. Ran with the wrong crowd a bit. One day when I was suspended from school, I actually read the autobiography of Malcolm X and was really taken by the way he transformed his life and became such a global leader, and it made me feel like I could also do the same thing, and I fell in love with books and I wanted to pursue a similar type of career fighting for civil rights. And it wasn’t lost on me that when he was ultimately assassinated, he was working at a campaign to go to the United Nations and to fight for the civil rights and human rights for Black Americans using the United Nations as a platform to do so. So that’s always been a dream of mine to take that global approach and that global perspective and to try to continue to fight for civil rights using that approach.

So when I went to Howard, I studied under some wonderful professors. Dr. Greg Carr is one professor I can mention. Under him I actually began to research the life of Marcus Garvey and worked on some scholarship, and I ended up traveling to Jamaica to do more research on a case where he was wrongfully convicted of mail fraud. I went to Brazil for a study abroad program comparing Afro-Brazilian and African American culture. And ultimately, I did my Fulbright in South Africa studying the life of Nelson Mandela, particularly his time as a lawyer who was also an organizer fighting for civil rights.

So for me, taking all of those perspectives and using those stories as inspiration was something that I always wanted to do with my career as an activist and as a professor. I teach now at the law school and I teach critical race theory and I teach classes that, for me, really seek to, in the same way I was inspired by learning of the story of Malcolm X as a young person, I would love to inspire other young people to teach them about our history and how they could be civil rights advocates.

So for me, that has been a long journey. Really reached its apex when, while teaching in St. Louis, I lived about 10 minutes away from where Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, and had a chance to help to represent the family of Mike Brown as they began to advocate for justice, and we ultimately went to the UN and advocated for police brutality to be seen as a human rights issue, not just a civil rights issue, but something that people around the globe should pay attention to when it happens to people in the U.S. and around the world. So that was one of the highlights of my career and it really started to give me the idea that I could do more than just study about people in history who have worked on these issues from a global perspective; I could actually do something to be part of a solution. So that got me to the place where I am today.

MS. BRAZILE: That is a good journey. Madam Ambassador, let’s discuss some of the most important – let me just say, some of the past leaders like Ralph Bunche and of course Ambassador Perkins, who served under the Reagan administration who played a very crucial role in the Free South Africa movement, how do you – when you’re in a classroom or when you’re talking to students about some of these prominent Black Americans who have served in so many capacities overseas as our representatives, how do you describe their role and their responsibility and the changes that they have made on the international landscape?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: I am in awe of their role. I walk past the Ralph Bunche Park when I’m walking to the UN on some mornings, and every single time I pass that park I think about the extraordinary role he played, but the path that he laid for me and others to come into diplomacy. And what is surprising to me is that so many young people don’t know who he is. And so we need to do a better job, my generation and your generation, we all need to do a better job of making sure that these icons are not forgotten.

And then Ambassador Perkins is really special to me. He’s from Louisiana, by the way, and he was my mentor. I liked to tell him – he passed away last year – but I liked to say to him that he lifted me out of obscurity and brought my career forward. I was very content being obscure. (Laughter.) And he brought me into his office when he was director general of the Foreign Service to be his staff assistant and then his special assistant, and it lifted me up in ways that I can’t even describe. And then I would go on in my career, over a few years, and then become the ambassador to Liberia. And when I arrived in – at the embassy in Liberia, there was this long hallway of Black faces going back to the 1800s, but it – one of the faces was Ambassador Perkins. And so every single day when I walked through that hall looking at all of those former ambassadors and then looking at Ambassador Perkins, he always gave me courage for whatever I might have to deal with that day.

I would later become the director general of the Foreign Service, a position that he had, and then to be Ambassador here to the United Nations, another position that he had. So he really has guided my career. He’s laid the path for my career. His being appointed as the first African American to be ambassador to South Africa was historic, done during the Reagan administration. He got a lot of criticism for that. But if any of you know him, you ever saw him, he was a powerful presence and he was a powerful man, and he was a Black man, and he was able to go to South Africa and lift up Black people and ensure that they got the recognition that they needed. And he was a voice in the administration – and many criticized the Reagan administration, but he was a voice in that administration that led to many changes in policy, and he was certainly a voice of hope for South Africans. I remember him telling me going every day to the trials of South Africans. His book is sitting now on my bookshelf, and when young people ask me what they should be reading about diplomatic careers, read Mr. Ambassador. It’s an extraordinary life story starting with him as a young man growing up in Louisiana and seeing him go from there to becoming what he became. And the fact that I have done some of the same things that he has done, for me, is extraordinary. And I give him full credit for having brought me this far.

MS. BRAZILE: He was an incredible leader, and I have to tell you that in preparing for this segment today that Justin reminded me that I should look at this PBS film called “The American Diplomat,” and it’s about an African American who has served in the diplomatic corps and he is featured in one of the stories. And I know, Justin, you can even tell it better, is when he went to South Africa, I believe he discussed his role, and at the time the president of South Africa said to him, “Don’t go anywhere, just stay in your” – basically “stay in your embassy and I’ll take care of everything.” And he said, “No, I want to go around and see the people.” And he did manage to do that.

So, Justin, talk a little bit also about Ambassador Perkins and Ralph Bunche and also the role that African Americans, Black Americans have played in so many of the struggles leading up to the Free South Africa movement and other important initiatives.

MR. HANSFORD: Yeah, definitely. It’s such an interesting path that Ambassador Perkins had to both represent the United States and to challenge the United States on issues of human rights, and it’s a delicate balance. In many ways, some of us who have been advocates our entire career could focus on the challenging part, and a lot of the history of advocates who have used the global stage to fight for human rights involves building on the legacy of people like W. E. B. Du Bois who helped to draft the We Charge Genocide Petition to the United Nations advocating for reform and, ultimately, the overturning of Jim Crow segregation. It was actually Paul Robeson who helped to deliver that petition to the UN, and Claudia Jones and other activists way back in 1951.

And even moving into the 1980s, as we talked about the Free South Africa campaign, there was an organization called TransAfrica led by Randall Robinson and so many people – Mary Frances Berry and others, scholars and activists – contributed to playing the outside part of that inside-outside game, if you will, being willing to protest the embassy here in South Africa – here in the United States, to try to make sure that sanctions could be imposed on the South African Government until Apartheid was overturned. And those sanctions that Black Americans helped to advocate for played an important role in leading to the freedom of Nelson Mandela and the end of Apartheid.

So there is a very interesting legacy of both people working inside of the United States Government as ambassadors and Foreign Service officers, and also people who are advocates willing to use that global platform and acknowledging that America is – the way America treats its citizens and the way America treats Black people around the world are issues that are relevant for us to advocate about and to ensure that we can create as much human rights as possible around the globe.

MS. BRAZILE: Ambassador, let’s discuss the Permanent Forum on People of African Descent. And in many ways, it’s a fulfillment of that history in the form of a permanent seat at the table at the United Nations for Black people, and now Professor Hansford will be our representative on that forum. I believe you’re the only U.S. person. So can you share with us what this means and what do you hope will come out of Professor Hansford’s work on the forum?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: I hate to give you marching orders on this video, Professor Hansford. But I think for us, for us – when I say “us,” I’m saying for African Americans but also for us, the United States – having him participate in this forum brings the – will bring the voices of the millions of African Americans who came here as slaves, not as immigrants. Sometimes you’ll hear people say we came as immigrants. We were not immigrants. We were trafficked here. We were trafficking victims who were brought here to the United States, and so many people do not understand our history. And I think having Professor Hansford there, he will help this, what is a global organization that brings people from all over the world, understand the specific history that African Americans bring to this forum and the important role that we play in the diaspora community.

So I am looking forward to your participation. I’m looking forward to the results. I’m looking forward to supporting you as you participate in this forum and move the agenda forward so that there is a better understanding, a better appreciation for the people of African descent.

MS. BRAZILE: Madam Ambassador, you played a prominent role in securing this forum when it was in jeopardy. Tell us why it was in jeopardy and what can we do now to make sure that we – to make sure that it gets the kind of visibility and the kind of resources it needs to do the work that it’s supposed to do.

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: I mean, there were a lot of naysayers. There were a lot of voices out there that didn’t think this was necessary. They felt that there were other fora that we could deal with the issues of people of African descent. And we stood strong with partners to push for this agenda and to make sure that it stayed at the top. And I can tell you that you can look forward to us engaging to ensure that the forum gets the financial support that it needs and it gets the political backing that it needs to accomplish its job. And we don’t have a lot of time to do it. We have just a few years left, but I think we are committed to ensuring that the forum carries out the agenda that we all appreciate and expect that the forum will carry out. But I would love to hear from Dr. Hansford how he sees his role over the course of the next couple of years.

MR. HANSFORD: Yeah. Well, I have to say, first of all, thank you for all that you’ve done to secure this forum for us here in the diaspora, and of course Black Americans as well. For me, I see my primary role is one of establishing the longevity of the forum. This is brand-new. We have an Indigenous Peoples Forum in the United Nations that’s been around for 20 years, which is also called a permanent forum. And of course for us, not only do we want to see our 20 years match that, but the key word is “permanent,” right? The Permanent Forum for People of African Descent. And in order to do that, there has to be participation from grassroots activists, from the civil rights community, from the human rights community. It’s going to depend on the initiative, the imagination, even the indignation of people who are willing to stand up and make sure that this becomes a platform that is useful, and there’s a lot of things that we can do to make sure that it becomes a useful platform.

For me, I worry that we spend so much time as advocates putting out fires, so to speak. There’s so many different crises affecting people in the Black diaspora. I think we also need to make sure we have an affirmative agenda to make sure we fight for justice on our terms. And for me, one of the key issues that is involved in that is reparations. I’m an advocate for reparations. Of course, I’m someone who’s descended from enslaved people on both sides of my family, but it’s not just reparations for enslavement; we’ve got so many issues to discuss, from redlining to police brutality to environmental justice issues to health disparities. I think in all of these areas, we have to build on the ideas that were put forward by some of our forefathers, even thinking like Dr. King.

Dr. King always said that, in his “I Have a Dream” speech, that we were given a promissory note which came back marked “Insufficient funds” when we asked for justice for harms that were done to us as a people. And that’s part of the “I have a dream” speech that isn’t mentioned as often, but that is something that we have to begin to advocate for using the global platform and recognizing that in addition to segregation, colonization has affected people in the Caribbean, on the continent of Africa, and we are still experiencing the ongoing lingering effects of those injustices. So that is one of the things that I think we need to be able to address and exchange ideas throughout the diaspora on how best to address those past injustices and get to a place where we have repair, and perhaps we talked about truth and reconciliation – maybe reconciliation at some point so that we can really fulfill the mission of the United Nations, which is to create more peace and more fairness and more equality and more human dignity for people who are really in need of it around the world.

MS. BRAZILE: What’s the structure of the forum and how often will it meet?

MR. HANSFORD: The forum consists of 10 people, people from around the diaspora and around the world. We have not officially commenced with the work of the forum, so to speak. We have had initial meetings, but we still have to set the groundwork; we still have to decide how often we’re going to meet, for example. So we do know that we will have at least one yearly meeting. This year we will have a yearly meeting in November, but our plan is to have at least one meeting in conjunction with the United Nations where we invite civil society, grassroots activists from around the diaspora to come and discuss with us all of the issues that they’re facing, and specifically the issues that they think the United Nations can be of service to help to address.

So the Indigenous Peoples Forum has the same yearly meeting where three, four, or five thousand organizations come together and they have music and they have food and they have a big celebration, and they also have a lot of important discussions, and they discuss the issues that affect the indigenous community globally and they discuss ways that the United Nations can be of support in responding to those problems.

So our goal is to use that same model and to bring people together from around the diaspora, have some great get-togethers socially, but also to have some great discussions that really hash out issues, put forward best practices, convene our experts, our scholars, convene people who are politicians or people in the business world and people who can help to bring us to a point where we can get justice and even get more development and more resources for people throughout the diaspora so that we can more effectively live out the mandates of the United Nations declaration for human rights for all people.

MS. BRAZILE: Madam Ambassador, there are so many human rights issues now in the forefront of the United Nations, including the refugee crisis in Haiti, the Sudan, Ethiopia, of course human trafficking which you mentioned earlier. How would you go about making sure these issues are addressed within the forum, and what role should civil society play in helping to make sure that we can somewhat back you up so that they can be addressed?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: First and foremost, civil society’s role is extraordinarily important. And we fight here in New York every single day to make sure that NGOs and civil society voices are not suppressed at the United Nations, and particularly at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. Without civil society, we don’t have the muscle that we need as countries to fight for issues of human rights.

For the United States, as you know, human rights is a core value. We put human rights at the forefront of all of our engagements. You know that even just this month, we brought forth a resolution in the General Assembly calling out Russia for human rights violations in Ukraine, and we won a resolution that suspended Russia from participation in the Human Rights Council in Geneva because of the atrocities that they are committing in Ukraine. We raise human rights issues as it relates to China and the genocide that is taking place in Xinjiang against the Uyghurs. We raise human rights violations wherever they take place, anywhere in the world.

And I will say that sometimes it’s thrown back at us, because we’re not a perfect nation ourselves. But one thing that every member state in New York knows is that we don’t shy away from self-criticism. We don’t shy away from acknowledging where we have shortcomings. And sometimes I’ve been accused for apologizing. I have never apologized, but what I have done is acknowledge the weaknesses in our democracy, which is still, even 200 years in the making, our democracy is still not perfect and it is a democracy that is always self-correcting. I think it was the President who said the great thing about democracy is that it can self-correct, and that’s what we try to do every single day. But it doesn’t mean we can’t raise human rights violations elsewhere, we can’t raise problems that exist related to racism elsewhere because we have racism in our own country. We acknowledge those issues. We do have mechanisms to address those issues, and certainly our voices are never forcibly shut down when we speak about our own country.

But we want to make sure that we engage others, and you know that we were not a member of the Human Rights Council under the previous administration, and President Biden made it a commitment that we would immediately rejoin the Human Rights Council when he came in on January 20th, and we did get re-elected to the Human Rights Council in June of last year.

MS. BRAZILE: Are there any issues that you are focused on at this moment in the development of the forum?

MR. HANSFORD: Well, I think that – oh, go ahead.

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: No, over to you.

MR. HANSFORD: Okay. I was just going to – one thing I wanted to agree with you with is that as we develop the forum, it’s important that we use it as a space to build new solutions and to exchange ideas and don’t let it be limited to a space for criticism. There are people in the forum from – who are speaking on behalf of Black people in the Caribbean, on the continent of Africa. There’s a member from Switzerland. And so in each of these different contexts, there are issues. Indeed, in some of the countries on the continent, these are Black governments with human rights issues that are affecting Black citizens.

So there are many places where we will find deficits, but I want to focus on deposits. I want to focus on solutions that we can bring by exchanging notes, by exchanging information, by traveling around, speaking to experts and coming together in a way that if we exchange ideas and if we’re a group people with resources convening power and the ability to – and desire to use the UN – this huge global institution, one of the most powerful institutions in the entire world – if we can actually use some of those resources to find solutions and build a better world for people of African descent, I think we will really be going a long way to fulfilling our mission.

MS. BRAZILE: So we’re going to put a spotlight on religious conflict and environmental concerns as well as maybe inequality. Is that something that we – the forum will address, Madam Ambassador?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: I absolutely hope so, and I think it is within the parameters of the forum to address because people of African descent have experienced issues because of their color as it relates to how we deal with climate change. We know that in Louisiana the Cancer Belt affects more African-Americans than it does anywhere in the world, and that’s an environmental issue that has to be addressed that has a racial component to it.

We know that as we look at the impact of climate change on the continent of Africa that the impact is sometimes played down on the continent of Africa because we’re not raising our voices. And we need to raise the issues of climate change. In the Security Council this past year, we were looking at the impact of climate change on security. We see major security issues occurring in the Sahel related to climate change. There are a whole bunch of reasons why there’s insecurity, but climate is one of them because we’re seeing that the desert is moving rapidly southward and we’re seeing clashes between pastoralists and agriculturalists because of the – because of climate change. So all of those issues ought to be in play as we look at how we address the impact on people of African descent.

MS. BRAZILE: Will gender equality also be a topic of concern with the forum?

MR. HANSFORD: Certainly. I think that the question of gender equality not in the United States but throughout the Black diaspora is one that we’re continuing to see the effects of. I know in France, for example, it’s a society where there has been a great deal of oppression, specifically of – with Black Muslim women who are being targeted for wearing the hijab. We know that in other parts of the Caribbean and Latin America there’s major issues with domestic violence.

The one interesting thing that I found in some of my preliminary discussions with members of the forum is that there is a need for data collection. There’s a need for resources to be put forward for surveys and research, because outside of the United States there hasn’t been as much of an emphasis on exploring not only the disparities but even the presence of some of these problems to begin with. And in some places like France, they don’t even keep records as to demographically how many Black citizens they have, and also I believe in Costa Rica it’s the same issue.

So there are many different ways that we can address these issues, and again, use some of our expertise here in the United States for people who have taken approaches to try to solve these problems and research these problems so we can get to the solution. And so, it’s not only a question of us receiving – here in the United States receiving information and receiving solidarity, but also giving to the best of our ability any sort of information that we can to people throughout the diaspora who are also aspiring to achieve more human rights.

MS. BRAZILE: Madam Ambassador, you —

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: You want to make sure —

MS. BRAZILE: Go ahead. No, go ahead.

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: We want to make sure that as we look at issues of women’s peace and security that it’s also African – people of African descent, women of African descent are incorporated into those discussions. Because while we have a number of forums that deal with women’s issues, they don’t always look at how these issues impact people of color. And so, I think there is a role for the forum to play in ensuring not necessarily that the forum itself address these issues, but making sure that the other forums that have been set up to address these issues don’t ignore women of color.

MR. HANSFORD: That’s right.

MS. BRAZILE: Madam Ambassador, I wanted to go back to your role when you were the director general of the Foreign Service. How do we increase the number of women, minorities, and others in the Foreign Service?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: Well, first and foremost, we have to recruit them. And we have to actively – proactively recruit. And sometimes when I was director general of the Foreign Service, I would say it’s really too late when they’re in college, when they’re – when they are walking across the stage to get their degrees. We have to recruit them in eighth grade. And I also use eighth grade because I feel like I was recruited in eighth grade because I learned about the world in eighth grade. I learned that there was something bigger than where I was. So, it’s about exposure of young people. It’s ensuring that they get language skills when they are young so that they are prepared to take on these positions and they are familiar with the positions.

I can’t tell you how many young people don’t know – women and people of color here in the United States are not aware of the opportunities for them to work at the United Nations. They’re not aware of the opportunities to work in foreign affairs in the State Department. We do have some incredibly successful programs in the State Department. Howard University has been engaged with us for years working on the Pickering and the Rangel program where we bring young people in a scholarship, and they actually study and work to prepare themselves for careers in foreign affairs. But that’s the first step. That’s not enough.

The second step is retention, and I think sometimes we fail at the retention side. I can tell you that when Ambassador Perkins pulled me out of obscurity, I probably – if he had not done what he did, I probably would not be still in the Foreign Service. I probably would have spent 20 years in the Foreign Service and retried unknown to anyone, never having made – had an impact. So, it is important for mentors and sponsors to reach over and down to young people and encourage them, lift them up, sponsor them as I was by Ambassador Perkins so that they can see their career path moving forward.

And there were times when even after being lifted up by Ambassador Perkins that I doubted whether I wanted to stay in the Foreign Service, and I doubted whether I was good enough to stay in the Foreign Service. So, it was useful seeing other people who look like me: Ambassador Brazeal, who was my ambassador in Kenya when I served in Kenya; Ambassador Ruth Davis, who was also the director general of the Foreign Service; seeing other women achieve what I would hope to achieve. And I know that I have to be a successful role model for other people of color, for women to see that there is a successful career path that they can follow.

MS. BRAZILE: You are indeed a role model, and I hope one day somebody will write your book and maybe I’ll play a small role to just encourage you to start getting your notes together. I want to —

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: Thank you.

MS. BRAZILE: Yes, ma’am. Justin, Professor, you said: “If confirmed,” and of course you’ve been confirmed, “I hope to involve the entire Howard University campus – students, staff, faculty – in this project.” How would you go about doing that and what can students do now to help you, and the faculty as well?

MR. HANSFORD: Well, they’ve already begun helping, so that’s the good news. We’ve got our Ralph Bunche Center for International Affairs here that has already taken the lead in collaborating and finding ways for us to host evens here on the campus. I’m looking for students who are interested in interning, whether they be graduate students, undergraduate students, law students, finding ways for them to begin their path towards a career in international affairs by helping with this project and helping us launch this and get this off the ground. I’ve got a clinic I teach over at the law school. We actually had 40 eighth graders over today at the law school —

MS. BRAZILE: The eighth graders.

MR. HANSFORD: — incidentally, so eighth graders on our mind. And we’re talking to them about Pauli Murray and intersectionality and Black women in the law and Thurgood Marshall and Charles Houston of course, and of course we were talking to them about the UN Permanent Forum and all of the possibilities that exist there. And we certainly will be using my clinic this upcoming year to do more work.

We have students who are in law school in their second or third year who have an opportunity not just to study law but to actually get their hands dirty, so to speak, in terms of the practice of law. And they’ll be doing work for us with the Permanent Forum through the mechanism of the clinic.

So many – we’re just – we’re looking for more ways to involve students, staff, and faculty every day. We’ve got wonderful faculty, as you well know, who are already deeply engaged in the project of advocating for human rights on the global stage and working at the UN. There’s a long legacy of that here at Howard. So I’m looking forward to collaborating with those faculty, collaborating with the Ralph Bunche Center, collaborating with the students as much as we possibly can.

MS. BRAZILE: Thank you so much. Madam Ambassador, in the few minutes we have left, can you just give us an update on the situation in Ukraine? We know it’s changing every day when we hear that Russia is now focused on capturing the eastern and southern parts of a sovereign nation. What is the latest on the situation in Ukraine?

AMBASSADOR THOMAS-GREENFIELD: Thank you for asking that question because I spend a lot of time on Ukraine. We’re only eight weeks into this war and the devastation that the Russian military and the Russian Government has wrought on the people of Ukraine is indescribable. So right now as we speak here at the United Nations, we have spent these past two months in, one, isolating Russia, and I think we have successfully done that; we have supported Ukraine – a U.S. Government policy – making sure we give them the support that they need to fight; and we have unified the world in supporting this effort.

And I think the Russians were not expecting that. I think what they expected when they went into Ukraine on the 24th of February was that they were going to go in, and they were going to bring the Ukrainians down to their knees in a couple of days. The Ukrainians would come out waiving a white flag of surrender. And they would go about making this country into a Russian-controlled state. They failed at that. And so, what they are doing at this moment is they have done some rethinking about their approach, and they’ve moved their troops around to the East of Ukraine in an effort to solidify their control over the Donbas and Luhansk region where they already had troops, and try through their aggressive and unrelenting attacks on Mariupol, connect that Donbas region to Crimea where they are also in control.

They have blockaded the Black Sea. And in that blockade, they’re keeping essential humanitarian assistance and food assistance and supplies that might be going to other places in the world, including Africa, they’re blocking the path. They’re arguing to the world that people are feeling the effects of what is happening because of our sanctions on Russia, and that is the furthest from the truth. They’re feeling the impact because of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. They’re feeling the impact because Russia is blockading Ukraine. It still has food that they are prepared to ship all over the world, as they have done in the past.

We have seen 10 million people be forced – 11 million people, in fact, be forced from their homes. Five million of them are refugees in bordering countries and the other 6 million have been stranded and are displaced inside of Ukraine. And they’re being terrorized every day by these Russian attacks. So, the situation there is still ongoing. I engage almost on a daily basis with the Ukrainian PR, with the other members of the Security Council to keep us unified in isolating Russia here.

The Russians have also ramped up a campaign of propaganda and disinformation that they are spreading around the world, noting that what they are involved in in Ukraine is a military – a quick military action. And what is in fact happening is a war, and they’re denying the fact that it is a war. And they are trying to distract the world from focusing on what is happening in Ukraine, including distracting Russians themselves who are not aware that their boys are being killed in Ukraine fighting this unjust war.

And one of the things I heard – I visited the region a few weeks ago. I was in Moldova and Romania, and I had an opportunity to meet with the leaders in both of their countries but also to meet with the thousands of refugees who have fled for their lives. And almost all of them are women and children who have left their husbands behind fighting. And what struck me in those discussions is while we’re focusing on the destroyed buildings, the images that we see every day on TV including today, there are people whose lives have been destroyed. And I – and in terms of the figures of people who have died, we don’t know what those numbers will end up being. Russia has not responded to efforts to find a diplomatic solution.

As you know, President Biden tried for months to negotiate and discourage President Putin from taking this action, including threatening him with sanctions beyond anything he’s ever experienced before, and those sanctions are being imposed on the Russians as we speak. And the international community has been unified in supporting those sanctions. The Ukrainians are still pushing for a negotiated settlement with the Russians. Putin announced recently that the negotiations were going nowhere because his intent is to bring this country to its knees. But the Ukrainians have shown extraordinary courage and grit in fighting this war.

MS. BRAZILE: Madam Ambassador, thank you so much for spending time with us here on the campus of Howard University. And I also thank you for your incredible leadership in representing the United States before the UN. Professor Hansford, we are looking forward to working with you and the UN Permanent Forum for the People of African Descent, a global space for all people of African descent to come together to build a better world.

Unfortunately, we’ve run out of time. And I want to thank everyone for joining us today, especially Ambassador Greenfield-Thomas (sic) and Professor Justin Hansford. Let me also thank the team here at WHUT-TV for hosting us this semester. We deeply appreciate all of your help.

Finally, to the students, to the faculty, to all of the administrators here at Howard University, you have been an amazing and really an incredible partner that I’ve enjoyed working with over these past four years. Once again, let me personally thank Gwendolyn and Colbert King for their generous support and leadership in creating the King Lecture Series. Colby King I know would be proud of me saying that he worked at the State Department and it was one of the most important aspects, and he’s had so many great career accomplishments, but I know – I had to do this one for Colby King as well.

We’re immensely proud and thankful that you were able to join us today in this important conversation and to help shine a light once again on Black excellence, especially when that excellence stems from Howard University. Thanks again. It’s been my great honor serving as chair of the King Lecture Series. Thank you.

Original source can be found here.