In May of 1941, my fifteen year-old maternal grandfather returned to the United States, the land of his birth, to earn money to send to his family in Japan. Seven months later, the country of his birth and the country he called home entered into a terrible war, preventing my grandfather from reuniting with his family for twenty years. Both my grandparents, as U.S. citizens of Japanese descent, were rounded up and imprisoned in camps for the duration of the war and left to start their lives from scratch when they got out. They found each other, got married, began sharecropping in California - growing strawberries to sell at a roadside stand - and went on to raise a large loving family with five children and seven grandchildren.

Growing up, my cousins juxtaposed this story of adversity and separation with how we saw our grandparents (baa-chan and jii-chan), who enjoyed throwing family parties, supporting local sports, and watching sumo wrestling on TV. Although their ability to overcome this adversity was a point of family pride, how could they possibly not be emotionally devastated by their experiences, and how had they managed to soldier on? My baa-chan explained to us the concept of “shikata ga nai" - which loosely translates as “it can’t be helped." Many Japanese Americans during the war took on this attitude of accepting that some things, like having their loyalty questioned and their rights as citizens taken away, were outside of their control. Instead, they focused their work, their energy, and their love on the things that they could control.

I thought a lot about this phrase as I worked as a consular officer to assist U.S. citizens in Spain at the outset of the pandemic last March. Overnight our phone lines and inboxes were flooded with desperate calls for help from citizens trying to make sense of border closures, lockdowns, flight cancellations, and forced separations from family. I drew upon the shikata ga nai part of my Japanese American heritage to come to terms with the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic, Spain’s police-enforced lockdown, and canceled visits with my parents were all out of my control, allowing me to focus my energy on assisting my fellow citizens.

My heritage has not always made my work as a diplomat easier. As a multiracial Black and Japanese American, I don’t look like what a lot of my interlocutors expect me to look like. While working as an economic officer in Burundi, children would point and shout “chinois" (Chinese) and “nihao" (hello) at me, and some local officials I met with would directly ask if I, a representative from the U.S. embassy, was American or not. It sounds ridiculous, but this kind of thing happens in the United States too. Many Asian Americans have had the experience of their fellow citizens questioning their nationality, their loyalty, or their identity.

The beauty of shikata ga nai is not in acquiescing to what you can’t control, but in focusing on what you can control. Pushing back on discriminatory treatment of people based on their heritage is in my control in a way that it was not for my grandparents. I have been proud to help increase the diversity of the State Department, adding different policy perspectives based on my background, and also shaping what people at home and abroad think America looks like.

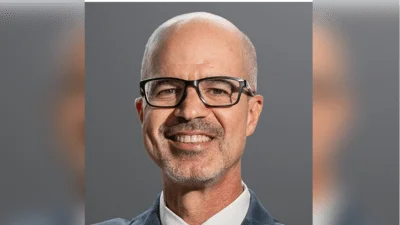

About the Author: Bryan Kenji Schell is currently serving as Staff Assistant for the Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa at the U.S. Department of State. His previous assignments include the Bureau of African Affairs, U.S. Consulate General Barcelona, and U.S. Embassy Bujumbura.