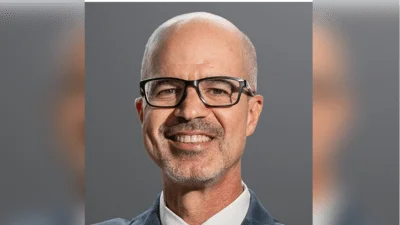

National Institute of Standards and Technology scientist Gary Zabow accidentally stumbled upon a potential transfer printing process for microprinting.

Zabow used hardened sugar as a way of transporting microscopic magnetic dot patterns to be used for semiconductor chips when he accidentally left one behind and noticed the pattern remained when the sugar was dissolved and rinsed away, according to a news release issued Nov. 25. Sugar readily dissolves in water, freeing the magnetic dots for Zabow’s research without dispersing any hazardous chemicals or polymers.

“The semiconductor industry has spent billions of dollars perfecting the printing techniques to create chips we rely on,” Zabow said in the release. “Wouldn’t it be nice if we could leverage some of those technologies, expanding the reach of those prints with something as simple and inexpensive as a piece of candy?”

Microprinting — the process of applying exact, minute patterns to surfaces that are millionths to billionths of a meter broad to give them new properties — is essential to the production of semiconductor chips and other electronics, the release reported. These intricate networks of metals and other materials are typically imprinted on flat silicon wafers. But as the potential for semiconductor chips and intelligent materials increases, it becomes necessary to print these complex, minute patterns on brand-new, non-traditional, non-flat surfaces.

The method worked well for a variety of surfaces, including writing the word “NIST” in microscale gold lettering on a single strand of human hair and printing onto the point of a sharp pin, the release reported. Another instance involved the successful transfer of magnetic disks with a diameter of 1 micrometer onto the floss fiber of a milkweed seed. The magnetically printed fiber responded to a magnet, demonstrating that the transfer had been successful.