Chinese-owned Smithfield Foods is closing its production facility in Vernon, CA and reducing its sow herds in the Western United States, it said in a news release.

"The company will decrease its sow herd in Utah and is exploring strategic options to exit its farms in Arizona and California," the company said.

It cited the "escalating cost of doing business in California" for the changes.

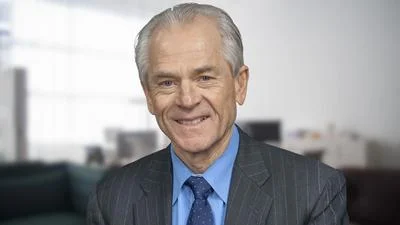

"We are grateful to our team members in the Western region for their dedication and invaluable contributions to our mission," Smithfield Chief Operating Officer Brady Stewart said in a statement. We are committed to providing financial and other transition assistance to employees impacted by this difficult decision."

Smithfield will serve California customers with its Farmer John brand and "other brands and products from existing facilities in the Midwest," the news release said.

China's WH Group Ltd purchased Smithfield Foods in 2013 for $4.7 billion, Reuters reported.

More than 500 North Carolina residents, most of whom were black, filed lawsuits in 2014 against Smithfield, citing the company's practice of storing hog feces in open pits, Agriculture.com reported. The North Carolinians, who lived on farms neighboring a Smithfield facility, stated that at times they were unable to leave their homes because of the stench, the story said.

In 2018 and 2019, jurors determined that the plaintiffs from the neighboring farms should be awarded $550 million, but a North Carolina law limiting punitive damages knocked that figure down to around $98 million when Smithfield settled in 2020. Judge Stephanie Thacker wrote for the court that Smithfield “persisted in its chosen farming practices despite its knowledge of the harms to its neighbors, exhibiting wanton or willful disregard of the neighbors’ rights to enjoyment of their property."

Attorney and author Corban Addison detailed the North Carolina trials in his book "Wastelands: The True Story of a Farm County on Trial."

Addison wrote of the North Carolina region, "there are five million hogs and only two hundred thousand people, many of them poor and Black."

Addison described the situation further: "All those hogs generate an unfathomable amount of waste, equivalent to a city twice the size of New York. Yet the method of waste disposal that Smithfield uses at all of its company-owned and contract hog farms--close to two thousand across the state--is as antiquated as an outhouse. Back in the eighties and nineties, the company's hog-producing forebears dug holes in the ground the size of Olympic swimming pools and dumped billions of gallons of feces and urine into them. When the "lagoons" reached capacity, they hooked up pumps to giant spray guns and turned them on the surrounding fields, converting what once was forest and farmland into waste-deposit sites... the industry has despoiled waterways across eastern North Carolina and befouled the air and land in dozens of communities."