Ukraine is fighting against Russia while confronting internal challenges like corruption scandals and foreign pressure over peace plans. Tymofiy Mylovanov, president of the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), says Ukraine must train ethical leaders, fight disinformation, and respond to corruption if it hopes to secure victory and long-term stability.

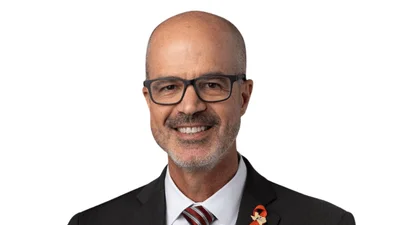

Mylovanov leads KSE, serves as a fellow at the University of Pittsburgh, and previously served as Ukraine’s minister of the economy.

According to Mylovanov, KSE was transformed by conflict. “I think we’ve grown over nine times in enrollment during the four years of the full-scale invasion,” he says. KSE expanded from a graduate-only institution of about 300 students to 2,000, with more than half now undergraduates. “Only 31% of students are in economics,” he says, noting a heavy shift toward STEM fields such as software engineering, math, psychology, and urban studies.

Students give him hope. “The percentage of students who stay in Ukraine after graduation has increased from about 50 to 87,” he says. Students are free to leave but “choose not to leave,” which he interprets as evidence that KSE is forming “a cohort of future leaders or current leaders of Ukraine.” Many arrive with strong ethics and patriotism, and he sees the school’s role as providing “the tools to change the country.”

The war has also drawn attention to KSE, he says. “Ukraine now is a part of the world in which history is made, in which in real, physical terms, democracy is defended.” That has brought new faculty, students, and donors, and Mylovanov believes institutions thrive when they create value. “If you do a good job, if you offer a product which matters for society, you will have funding.”

KSE’s role extends into humanitarian work. The school’s foundation builds shelters in schools, assists displaced people, and trains businesses damaged by the war. “We’re doing a lot more than classic university work,” he says.

Mylovanov’s public communication has grown just as quickly. He now has 170,000 followers on X and says the audience comes for policy and international affairs. He created a strategic plan for his communications with two goals. “Not to allow the world to forget the truth about Ukraine,” he says, meaning that Russia invaded and that tens of millions of Ukrainians “live daily lives in war.” His second goal is to bring attention and resources to KSE. He maintains consistency with a small team and AI tools that help him keep up during travel and exhaustion. “I’m very proud of myself,” he says. “It’s almost a technical thing, like consistency.”

The recent corruption scandal in Ukraine’s energy sector placed him in the headlines. For the first time, he explains why he resigned from two supervisory boards. Some officials at one company were implicated in a wartime corruption scheme. He says the board was honest but too slow. “Studying everything sometimes means inaction,” he says. The first days after the scandal broke convinced him the board “was moving too slow to address the issue.” He also wanted distance from a system where “people are getting hundreds of millions of dollars while people are dying.”

He now refuses to serve on any board without “a very clear action mandate in crisis.”

The scandal, he says, will be interpreted through existing beliefs. “If your initial belief is that Ukraine is corrupt, this proves you right,” he says. “If your belief is that Ukraine is fighting corruption… you also are correct.” What matters is the response. “What really matters is how the government and the president respond,” he says. Leaders must fire those responsible, fix procedures, and show they “learned the lesson.”

He applies the same lens to the controversy over a supposed 28-point peace plan that appears largely drafted by Russia. He calls it “very embarrassing” if the United States pushed it. “The United States is a great country, it should drive the process,” he says, and any settlement must avoid looking like “Russian propaganda rubber-stamped by the United States.”