American officials warn about great-power competition, yet many of the vulnerabilities lie inside state governments, campuses, and supply chains. Foreign adversaries buy land near U.S. bases, wire critical infrastructure with untrusted technology, and run influence operations in American institutions.

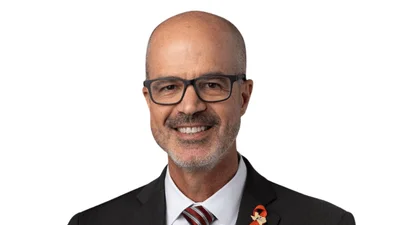

Michael Lucci, founder, CEO, and chairman of State Armor, says states must treat the China challenge as a direct security threat and run “stress tests” on their exposure.

Lucci grew up near Youngstown, Ohio, where shuttered steel mills and patriotic communities shaped his outlook. “I grew up in the Steel City, Youngstown, Ohio, and I had a lot of access to the outdoors,” he says.

Public service felt natural to him. Northeast Ohio, he says, is “an extraordinarily patriotic area” where people “just love the country.” He entered policy work after watching Chicago’s schools fail students. “Education was quite broken in the city of Chicago,” he says, and he concluded reforms required legislative change rather than more tutoring centers.

His understanding of political power took shape while watching long-time Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan. “He truly understands the levers of power,” Lucci says. When he later studied China’s behavior during the Trump administration, he recognized a pattern. “The Chinese side, their actions in their responses to Trump reminded me of Speaker Mike Madigan,” he says. That insight pushed him to consider how state-level authority could counter Beijing.

Lucci moved to Texas and saw the stakes firsthand. A retired PLA general quietly bought roughly 140,000 acres near Laughlin Air Force Base and the border. Lucci calls the land deal “certainly a provocation,” and credits Texas lawmakers for passing the Lone Star Infrastructure Protection Act to keep foreign adversaries off the grid. The episode convinced him “they’re really coming here.”

State Armor now helps lawmakers in multiple states pass what Lucci calls a top-ten security agenda, led by a “specific conflict stress test.” Nebraska became the first state to adopt it. Officials there examined how a Taiwan crisis could disrupt supply chains or expose critical infrastructure. Nebraska’s importance is clear, Lucci says, because “the majority of our land-based nuclear deterrent is in western Nebraska” and Strategic Command sits in the east—areas serviced by Huawei telecom equipment discovered by the FBI.

He says a real stress test naturally leads states to remove adversary technology from infrastructure, stop buying Chinese networked devices, restrict property purchases by adversaries, and protect genetic data by banning Beijing Genomics Institute. Testimony from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, he says, warns that Chinese cameras connected to operating networks “provide the PLA with the ability to fully take over those assets.”

Political influence is another priority. Lucci backs foreign-agent registration laws for adversaries, state laws against transnational repression, and broad reforms in higher education. Campuses, he says, are “wide open” to theft, harassment, and influence because “no one is looking.” He also pushes attorneys general to sue or investigate Chinese tech companies that “are beaconing data back to China” or allowing remote code execution in consumer and medical devices. “This is all fraud,” he says, arguing that China’s industrial footprint in the United States should be treated as a “military footprint.”

Resistance appeared quickly. After State Armor’s launch, Lucci says his devices experienced “technological glitches,” including switching into Chinese text. In Texas, he heard of a hacked livestream and a backpack bomb threat at a legislative hearing on the CCP. United Front activists sometimes flooded committee rooms to “harass people,” while business groups pushed back out of supply-chain anxiety or pressure from Beijing.

Lucci calls for alliances among lawmakers across states and nations. “We need to build alliances across the Western world,” he says, so that governments share information and coordinate policy.