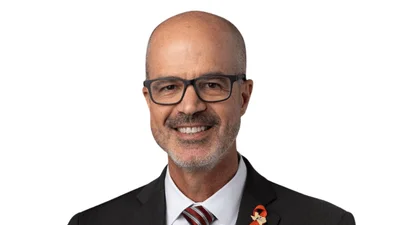

Leland Miller, co-founder and CEO of China Beige Book, argues that much of what the world thinks it knows about China’s economic trajectory is wrong, and he says understanding Beijing’s priorities requires ignoring official talk and watching how power, capital, and supply chains actually move.

Miller also serves as a commissioner on the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission. His China Beige Book produces the largest private survey of China’s economy and financial system.

Miller describes China’s economy as “weak, but it’s good enough for Xi Jinping.” He dismisses headline growth figures as political messaging. “Throw away the GDP numbers,” he says. “That’s just a political statement.” Survey data, he explains, shows weakness. “Not great, not good, but good enough,” he says.

Stimulus expectations, Miller argues, are deeply misunderstood. “The stimulus narrative is wrong, has been wrong, and will likely always be wrong,” he says. Beijing, he explains, learned from the debt explosion following the global financial crisis and no longer prioritizes growth for its own sake. “They have accepted the fact the economy is slowing down,” he says. “They don’t care about economic growth for growth’s sake.”

Promises of a shift toward consumption follow the same pattern. “They’ve been promising this investment-to-consumption shift for over a decade,” Miller says. He explains that investment slowed, but households were never empowered. “Consumption is against everything that Xi Jinping wants to do,” he says, citing financial repression and state control. Small programs, he argues, merely pull demand forward. “How many times do you need to buy a toaster and then trade it in and buy another toaster,” he asks.

Tariffs, Miller says, have reshaped trade flows. “Is it pleasant for China to have high tariffs? No,” he says. “Can it sustain these levels indefinitely? Yes.” Once tariffs exceeded roughly 60 percent, he explains, direct trade largely stopped, making higher announced rates irrelevant. “Commerce had already stopped,” he says. The result, he argues, marked a transition. “The U.S.–China trade war is dead,” he says. “Long live the supply chain war.”

Supply chains are now at the center of the economic competition. “You really have to have a strong focus on supply chains to understand the U.S.–China competition,” Miller says. He points to pharmaceuticals, electronics, and foundational semiconductors as areas where Beijing seeks leverage. “China has a national security prioritization,” he says. “We’re going to control as many high-value supply chains as possible.”

That focus defines what Miller calls China’s two-speed economy. “You have a broad macro economy that is substantially slowing down,” he says. Another segment, however, thrives. “Advanced manufacturing, technology, biotech, AI,” he says, describing sectors aligned with Xi Jinping’s security priorities. “Those areas of the economy are going very, very well,” he says, even as households feel poorer amid falling property values.

Social pressures exist, Miller acknowledges, but narratives about an eventual collapse miss the mark. “We’re not seeing a society falling apart,” he says. Demographics pose long-term risks, yet automation softens short-term labor shocks. “A falling working-age population is actually countered by the rise of robotics,” he says.

Miller urges governments to rethink globalization. “Unfettered globalization without thinking about vulnerabilities ended up being a very dumb idea,” he says. Supply chain resilience, he argues, must override pure market logic. “Some categories should be security first,” he says, advocating trusted networks with allies rather than dependence on adversaries.

Miller warns that reducing tariffs without regard to effective rates could undo recent gains. “You will massively reverse flows,” he says. “And you’ve got yourself a problem.” Understanding China’s economy, he concludes, starts with one rule. “The one thing you really don’t want to do in China is listen to the talk if you’re not also checking whether they’re walking the walk.”