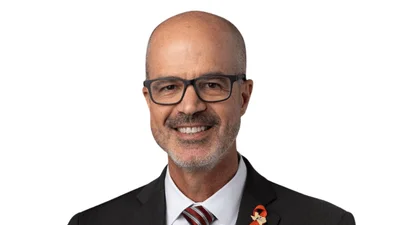

Weifeng Zhong, senior advisor to the America First Policy Institute’s Office of Fiscal and Regulatory Analysis, says artificial intelligence can reveal how autocrats telegraph their moves and how regulatory buildup has slowed U.S. growth.

Zhong grew up in mainland China during the reform era and moved to Hong Kong after college. The move, he says, transformed his understanding of his own country. He saw a sculpture commemorating the Tiananmen Square massacre and realized he had never heard of it.

He later earned a PhD from Northwestern University, worked at the American Enterprise Institute and the Mercatus Center, and helped create the Policy Change Index, an open-source project that tracks authoritarian behavior by monitoring shifts in state media.

The discovery in Hong Kong set the course for his work. Propaganda, he says, holds enormous power. “I said to myself, one of these days I am going to study propaganda coming out of the CCP, and that is exactly what I did.”

Encouraged by AEI economist Kevin Hassett, Zhong began building the Policy Change Index as neural-network tools became available. He started “harvesting every single word that ever came out of the CCP’s mouthpiece since 1946” to see how priorities changed.

Zhong focuses on deviations. “We do not care about whether it is talking about truth, because none of that is truth anyway,” he says. In tightly controlled systems, even small shifts reveal what leaders value. He compares the approach to judging a newspaper by what appears above the fold. “If you used to talk about thing A above the fold and now you talk about thing B, it means you care about thing B much more.”

Historical precedent strengthens his confidence. Zhong notes how Allied analysts in World War II monitored Nazi broadcasts for subtle linguistic changes. “There were traces in the language that deviated from the baseline,” he says. “It turned out to be a very good predictor of even the launch time of secret German weapons.”

He sees similar signals today. Russian state media shifted language before the seizure of Crimea and again before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Predicting endings, he says, is harder. “Predicting the ending might be fundamentally a different problem than predicting the beginning.”

He recently extended the index to North Korea by monitoring Rodong Sinmun. “Before Kim Jong Un put something major up in the sky, there were changes in the language too,” he says. He finds it striking that patterns emerge despite Pyongyang’s secrecy.

His curiosity predates the research. He traveled to North Korea in 2010 to see what China looked like before reforms. “The people there were terribly malnourished,” he says. “They tried to show us the absolute best side of the country, but even that was way worse than what I could randomly spot in South Korea.”

Experience with communism shapes his views in the United States. “Fundamentally, which is why I think I am a conservative in this country, I think communism is an extreme form of a lot of the liberal ideas we have here,” he says. “People are stupid, the party is righteous and knows where we need to go.”

His perspective also shapes his view of China’s WTO entry. He remembers accession as a moment of public optimism. “It would make us more open and more modern,” he says. His view now is that Beijing learned to exploit the system. “Instead of changing yourself to be better, you can corrupt the entire system and take even more advantage of it.” According to him, “Economic freedom is not the same as political freedom.”

At AFPI, Zhong now applies his analytical skills to Washington. “The U.S. government, in terms of policymaking, is like somebody who has had decades of very bad diet,” he says. “Now you are overweight, in very poor health, and all that is destroying the economic potential of the country.” He and his team “measure everything that goes on in the U.S. government,” especially taxes, spending, and regulations.

Using a model developed with regulatory scholar Patrick McLaughlin, they ask what would have happened if regulation had remained at 1980 levels. Their new study found “close to over $400,000, half a million dollars per head” in lost income from regulatory buildup over forty-five years.

Reversing that damage requires patience, according to Zhong. “You do not lose that half million per head overnight,” he says. Reform resembles an unhealthy person overhauling diet. “Even if you become a vegan the next day, it does not bring your probability of a heart attack down to zero.” The benefits come only after sustained discipline—and, in his view, measuring the regulatory state with modern AI is the first step.