The American health care system seems to be maligned by everyone because of always-rising costs, limited access, and persistent workforce shortages. In addition, health outcomes continue to lag behind other developed nations despite far higher spending. Robin Anderson argues that effective reform requires restoring the central role of primary care and investing in the relationships that make good care possible.

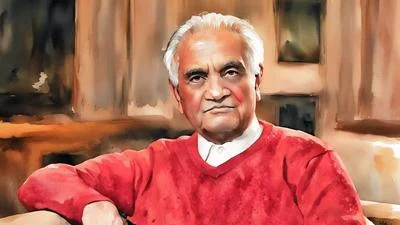

Anderson grew up and trained in Virginia, earning her medical degree from Eastern Virginia Medical School before completing a family practice residency at Washington Health Systems. She became a board-certified family medicine physician and built more than two decades of clinical experience providing comprehensive primary care through the Sentara Health Network in Virginia Beach. She now serves as president of the Virginia Academy of Family Physicians while continuing to practice medicine and advocate for patient-centered care across the Commonwealth.

Anderson says her decision to pursue family medicine grew from breadth and connection rather than narrow specialization. “I just loved everything, but there wasn’t anything that I absolutely loved,” she says. “As I practiced family medicine more and more, I came to realize that the relationships that I developed with my patients were really the thing that I loved the most.” Those relationships, she adds, often become the most therapeutic tool available to a physician. “That’s the most therapeutic thing in my tool kit, is my relationships. I love them and I love my patients.”

Continuity of care, she says, proves essential when medicine delivers difficult news rather than reassurance. “All the news we convey is not always the best news,” Anderson says. “When you have that relationship…even those moments of conveying the news that you would never want to give to somebody can be some of the most meaningful.” She recalls a patient telling her, “This isn’t news that I wanted to get, but I’m really glad you’re the one telling me,” a moment she says affirmed the value of long-term trust.

Anderson argues that many Americans misunderstand the structural causes of health-care dysfunction. Spending levels, she notes, already dwarf those of peer nations. “We’re spending 25% of our GDP on health care and quite honestly, we’re not getting a lot for that,” she says. She attributes much of that gap to underinvestment in primary care. “Our investment in primary care is the lowest rate of all of the developed nations,” Anderson says. “When you invest in primary care, you see better health outcomes.”

Lifestyle interventions matter, she says, yet they cannot replace consistent medical guidance. “I spend a lot of my time talking about people’s lifestyle,” Anderson says, while noting that cultural and societal barriers often make change difficult. Genetics and circumstance still shape outcomes, which makes honest dialogue critical. “When you have somebody that you feel comfortable talking about what you’re doing with your health…you’re ultimately going to be a healthier person,” she says.

Technology, she argues, should serve that relationship rather than supplant it. “If I have a patient who prefers telemedicine, I’m going to provide telemedicine as long as I feel I can do it safely,” Anderson says. She points to emerging tools that make remote care more viable. “There are digital stethoscopes…devices that you can look in people’s ears when you’re not in the room with them,” she says, adding that clinicians must still meet patients where they are.

Anderson says the Virginia Academy of Family Physicians focuses on responsible use of artificial intelligence, reforming prior authorization, and preserving medical liability protections. “I like a good AI tool, but it’s a tool,” she says. “It’s not going to replace a clinician.” She warns against systems that shift more administrative work onto already scarce physicians. “I would rather see another patient,” Anderson says.

Workforce shortages, she says, threaten the entire system. “There are definitely not enough physicians to meet the primary care need,” Anderson says, citing pay disparities, administrative burden, and cultural attitudes in medical training.

Debt and workload push many graduates elsewhere. “Medical students are coming out with about $300,000 worth of debt,” Anderson says, while primary care physicians often shoulder uncompensated tasks. “We answer a lot of messages that are not compensated because we care about our patients,” she says, describing late-night charting that clinicians call “pajama time.”

Policy fixes, she argues, must target incentives and support. Tuition relief tied to primary care service, reduced administrative burden, additional staff support, and expanded residency capacity all matter. She also highlights innovations such as accelerated medical school tracks focused on primary care. “If you know that you want to do primary care, a lot of the explorations…really aren’t necessary,” Anderson says.