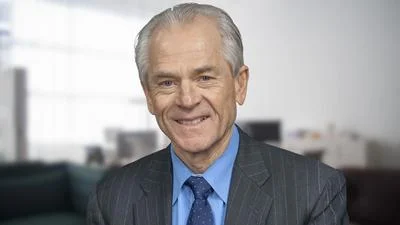

David Dollar is a Senior Fellow at the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution and host of the Brookings trade podcast “Dollar and Sense.” He served as an economic and financial emissary to China from 2009 to 2013 and at the World Bank, including as country director for China and Mongolia

China Desk

What were your early experiences with the Chinese economic model?

David Dollar

The time I spent in Beijing in the mid-eighties and China more generally gives me a somewhat unique perspective. Anyone involved at that point saw that China was extraordinarily poor and underdeveloped…and I can't exaggerate how poor it was.

I remember a day-long bus ride talking to a middle-aged woman sitting next to me. She was traveling village to village and just selling what I would call trinkets–combs, hair barrettes, simple things. She was so excited because, for her, economic reform meant she could travel around.

A lot of the reform was just really taking away restrictions that had been in place; letting farmers grow what they want to grow, and sell much of that output on a free market. So you suddenly have incentives to work harder and earn money or travel around doing a little selling.

Pretty soon we started getting people moving from the countryside to cities. I mean just so much dynamism that was essentially opened up by removing a lot of restrictions that had been in place about what people could do, what farmers could do, people moving.

China Desk

Was the Deng Xiaoping era the undoing of Maoism, and did it lead to the growth you saw?

David Dollar

We know from research that a lot of this bubbled up from below. This wasn't just a change in leadership at the top. Deng Xiaoping and others came in with good new ideas. A lot of the reform bubbled up from below.

Big reform in agriculture is just common sense. They had these agricultural communes that were not very productive, and they divided up the land and basically gave it back to family farmers. They got an immediate 20% increase in rice production, and a lot of that started at the local level.

People were not just poor, they were actually getting poorer during this time. During the Great Leap Forward or Cultural Revolution, you start getting communities that chose to go down this path of breaking up the communes and restoring something close to private property rights. They got the kind of response you'd expect from economic theory.

I give Deng Xiaoping a lot of credit for seeing some of this bubble up from below. He had the [wisdom] to endorse this as a nationwide policy. Then an important meeting [was held], I think it was December ‘78, where they endorsed this return to family farming, calling it the Household Responsibility System. So you're now responsible for your household. You're not just dependent on this commune where you work hard.

Of course, there were other reforms outside of agriculture, but a lot of the reform was taking away restrictions and returning to what I call private initiative. It may not have been exactly our private property rights, but it was a lot of space for private initiative.

China Desk

Can you explain the reforms through the 80’s and 90’s that fueled economic growth in China, such as the infrastructure projects that were made possible by American capital?

David Dollar

I want to make clear I was not personally involved in that early period, but I've studied it and I have huge respect for the colleagues at the World Bank who carried that out.

A couple of points. First, there was a famous trip by Robert McNamara, President of the World Bank, in 1980 [where he] traveled around and met Deng Xiaoping. Deng basically told him that China was going to modernize, and it was going to be successful, and it was going to do it with or without the World Bank. But it would do it faster with World Bank support.

McNamara was the first World Bank President who really threw the institution's support behind the Chinese effort. And there were many different components of it. I would single out macroeconomic policy, but I think the staff involved were very clever. They didn't try to lecture the Chinese, which is never going to be very successful.

What they did is they organized a lot of different events where they would bring in successful policymakers from other countries because, remember, China was quite isolated. It didn't have particularly strong diplomatic relations with many many countries around Asia, so the World Bank could play a useful role.

Actually the World Bank even brought in officials who'd been involved in the Taiwan Miracle, that's the kind of thing the World Bank could do. They could have an academic seminar bring in a retired and renowned economist from Taiwan and have that person just talk Chinese with the Chinese policymakers.

So Taiwan basically invented the export-oriented development model. That was a great lesson, but just more generally I think the World Bank facilitated contact between the Chinese policymakers and a lot of relevant different types of experts and experienced people around the world.

One story I love to tell is that one of the first infrastructure projects the World Bank did was a big port renovation.

They needed to buy those giant cranes you see in ports that lift and hold containers. China wasn't making anything like that back in 1980. The World Bank procedures require international competitive bidding for any big purchase like that and the Chinese were very reluctant.. We did international competitive bidding–the staff at the time, not me–that ended up costing about 20% less than the experts had estimated. [This was] based on going prices because all the relevant firms wanted to get into China, so everybody wanted to win this contract.

They got some kind of European contractor who won that bid, but the Chinese were really impressed and they ended up producing domestic procurement laws that included a lot of this element of competitive bidding, [and] of validating who's a reliable supplier, then having price competition to meet certain specifications.

So you have procedures that have been adopted in China because they were first done in a World Bank project. Then you develop the whole procurement system that has an enormous effect on the whole economy.

I think a lot of the effect of the World Bank is this kind of indirect, stimulating larger change in China that goes well beyond any one project.

China Desk

Can you tell us about your post 2000 China experience?

David Dollar

After China joined the WTO, it wasn't just that there was also a global boom going on and China had done a lot of preparation before joining the WTO. After 2001–I call this the Golden Age of Chinese–from about 2000 to 2008 the exports were going up rapidly. Foreign investors were coming in and the economy was doing well. People were getting richer, the housing market was taking off, so there was a very brilliant mood in China at that time.

I moved to Beijing in 2004 to head up the World Bank program which was no longer as important as in the early stage…It gave me an opportunity to travel all around the country and I brought my family to live in the suburbs of Beijing and there was actually a very nice international community that had developed, and there were quite a few different international schools. A lot of interaction between the foreign community and at least middle-class Chinese intellectuals.

While I was working for the World Bank, I would routinely teach classes over at Tsinghua University. I would just go over there and take over one of my Chinese professor friend’s class for a day and then come back a couple months later and do another day. I never really felt constrained in what I would talk about so there was a certain openness.

I wouldn't want to exaggerate it, but there was a certain openness at that point, a lot of at least active discussion on the economic front about where China should go next with economic reform.

I took over a World Bank program that was languishing a bit frankly, because its role was not really the same as it had been before. The main focus I put into the program was to try to help China with environmental issues, which were really just taking off at that time.

We did the first careful estimate of premature deaths from air pollution in China. That was very controversial and everything we did we had to discuss with the government and then get approval to publish. That's how the World Bank operates, and I worked pretty hard to get that report published.

In the end we did it together with Chinese scientists. It was based on good science that got published [with the] first credible estimates. We did some similar things on water.

We did a lot of environmental things. It was a moment where you were starting to get non-government organizations organizing around environmental issues, and also around AIDS. There was a little bit of space for civil societies.

These were not political parties challenging the Communist Party of China, but there was a little bit of space for civil society that was extremely welcomed by the Chinese population, and it made it a nice place to live if you were a foreign expert at that point.

China Desk

How is the structure of China today different from the previous decades?

David Dollar

I left the World Bank and joined the Treasury [Department] in 2009, but I stayed in Beijing and represented Treasury there.

I think the global financial crisis was another important turning point for China. The global financial crisis was a big tub of cold water thrown all over. China's exports dropped like a stone. 3 million workers were thrown out of work quickly. It was an extraordinary crisis and the government responded pretty effectively, but with their favored tool.

Basically they responded with a lot of money put into public investment. Infrastructure projects run by local governments and state enterprises.

If you think of that 2000’s period where the private sector was growing so rapidly that it was taking over more and more of the economy, after 2009 you had the reverse.

You had this big surge of state money going into certain things and then the private sector. A lot of that was in retreat first because of the global crisis. But also you start getting political change in the sense that you start getting some prominent Chinese entrepreneurs emerging as public figures in China.

A lot of them are in different aspects of the service sector– social media, alternative finance, online tutoring. A whole range of service sector activities, all of which are sensitive in China, finance, communication, media.

So, you get the Chinese leadership looking at the world and seeing that globalization has a lot of shocks and unpleasantness; and then also seeing that this rise of the private sector is starting to create potential political competition with the leaders of the communist party.

I see Xi Jinping emerging from that leadership. I don't see that it’s just a coincidence that he was chosen by his colleagues. Essentially, he's a pretty colorless bureaucrat. But I think he represents the elite level of the Chinese Communist Party pretty well, and they're afraid of power centers like the Chinese private sector developing too much. They're also worried about being too dependent on foreign technology.

You saw as their capabilities rose they were doing a lot of things in terms of cyber theft and intellectual property rights violation. You get a somewhat successful China starting to rebel against some of the norms of international capitalism. Then you finally get some response from the United States in particular reacting to that.

We've gone through a couple of cycles since back in ‘73 when Nixon visited China, and we're definitely now in a pretty bad part of the cycle where we don't like a lot of what China is doing. China doesn't like a lot of what the United States is doing.

These are two nuclear armed powers with enormous militaries, so there are a lot of risks and worries. Meanwhile, we still have a very high degree of economic integration.

So it's kind of a unique situation. We didn't have that with the Soviet Union, we just had the conflict and some detente because we didn't want to have mutual nuclear destruction. But with China, we have this extraordinary economic integration, and we have a lot of geopolitical tension on top of that.

China Desk

What should we make of China’s attempts to establish an alternative reserve currency and create a Yuan dominated trading system?

David Dollar

My short history of the Chinese currency in modern times is basically Communist Party leadership is very control oriented, they want to control the exchange rate. They don't like the idea of a market moving the exchange rate around very much. We've gone through a number of different periods where this was an issue when I was working for Treasury.

When I first joined, I would say the Chinese currency was pretty seriously undervalued and it needed to rise, and they were reluctant to allow that to happen. But gradually over time, there was a certain amount of appreciation.

I think they missed the opportunity to really liberalize, but they allowed it to appreciate enough to bring down their overall trade balance as a share of GDP. There was a little bit of policy success there…we got pretty good movement during my four years at Treasury, but that's just a coincidence.

More recently what we see is the market pushing their currency down, so you don't hear the US talking so much anymore about “why don't you liberalize the exchange rate? Because right now if they liberalized it, it's probably going to drop like a stone because people are losing confidence.

Chinese people are losing confidence in their own system. They want to move money out of the country. China has very strict capital controls limiting how much money you can take out of the country.

In that situation, I think most of the talk about the Chinese currency challenging the US dollar is just nonsense, because you don't want to get paid in Chinese Yuan. What are you going to do with it? It's not a convertible currency, you get paid in dollars. You can buy a 30 day treasury bill or you could buy a 60 day or 90 day. Whatever you need and then when you need to convert it say into Euros 90 days from now. There's a deep market for that.

You want to hedge so you can use the futures market to take any risk out of this. None of that exists, and dealing with the Chinese currency, I think the talk is really just talk.

Just to throw out a couple numbers, less than 3% of trade settlement is in Chinese currency. Most of that I would call just political. If Saudi Arabia essentially as a government sells a certain amount of oil to China, you know they're willing to take some payment and rent knowing that they naturally buy a certain amount from China.

It's almost like barter trade which is incredibly inefficient, but you don't see Saudi Arabia putting a lot of their extensive reserves into Chinese Yuan because of the problems I mentioned. You can't move it, there's no deep capital market or reliable property rights there.

So I think the dollar looks pretty solid for the long term, but of course we do have to preserve that. We've got to get our fiscal house in order and obviously we were bringing inflation down. People still have a lot of confidence in the US dollar, and I think that that's kind of self-fulfilling.

Last, I would say that if China made the kind of changes necessary to boost its currency like opening the capital account, having deeper, more transparent capital markets and futures markets, these kinds of things, we should welcome that because that would be an improvement for the whole world financial system.

I'm not worried about the dollar competing against the Chinese Yuan. But in the short run, it's not a serious competition because of their restrictions. If they want to remove some of that that would be fine with me. But I'm not holding my breath.

China Desk

What’s your assessment of the real estate bubble we’re seeing inside of China?

David Dollar

I think the main problem there is, they've overbuilt the housing stock.

Actually there are a lot of ironies in China. They've probably underbuilt the housing stock in their key cities like Beijing and Shanghai, but they don't let people move there very freely. If they opened up mobility there'd probably be a lot more space for construction in those tier 1 cities, but they've overbuilt the tier 3 and tier 4 cities.

There's more than a hundred cities in China with more than one million people. There are a lot of cities, and there's been big construction booms in almost all of them.

In many cases nobody's coming to live there. It's not attractive. There are no jobs. There's a real problem, and then the developers–mostly private developers–some of them are clearly in trouble. We've had a couple of essential bankruptcies. But, because of their control orientation, I think the leadership can prevent a financial crisis.

What you get instead is a kind of a growth crisis. It's just not going to be a dynamic part of the economy. It was as much as 25% of the economy going into building housing and things closely associated. That's a pretty big part of your GDP.

The first half of the year housing investment was down 20% over the past year. So you take a big chunk of your economy and you get negative 20, then nothing else you do is going to get you to a positive number.

That's why their economy right now looks like it's growing at about 3%, and a lot of that's just dragged down by the real estate sector.

I would expect the drag on growth to continue. But I would be surprised if there were a big visible financial crisis as we've seen in more genuinely capitalist economies.

China Desk

How does China’s current demographic projection change the economic model?

David Dollar

During that dynamic period, the urban prime-age working population went from 10 million to 400 million over a couple of decades. That's an extraordinary increase and an important part of the whole story.

Foreign investment and trade [are important], but you need workers and they had a pretty endless supply of people with good basic education, many of whom came from the countryside to the city. So you could get that extraordinary increase I mentioned, but that just comes to an end right now.

Basically the urban prime age population is going to be stable for a little while if they allow some continuing migration from the countryside to the city. But before too long it's going to start declining pretty sharply.

We don't really have any good examples of economies growing well once that prime working age population starts to decline.

Of course people are living longer there, which is wonderful, but it's going to be an economic burden taking care of all of the elderly with this diminishing workforce. I like to end up in the middle in a lot of these discussions on Chinese growth.

There's still a lot of positives in China, and if they could do certain reforms–[for example] allow people to move to the tier-one cities, which are the most productive.

Then there's certainly more things they can do in terms of opening up foreign trade and investment still. To be fair, they signed a big trade agreement with ASEAN, the Southeast Asian countries, and Japan, South Korea.

They could pursue more openness and allow more mobility, get away from this focus on state enterprises and respecting once again the private sector.

It's a pretty radical agenda right now in China. But there isn’t exactly a policy agenda that would certainly get them to a good healthy growth rate around 5%.

I think there's still a good chance China ends up as the biggest economy in the world. But it's just not going to be growing in the spectacular way we saw in the past.

China Desk

Is it really possible for China to achieve that mid-level growth and sustainment if they don’t open up to migration from outside of China?

David Dollar

I think all the big economies, including the United States, need immigration in order to grow healthfully, and I just don't see China as very welcoming to immigrants. They may have a declining workforce, but it has a huge population and a lot of barren land out in the west.

If you really look at where people live it's very densely populated and it's a pretty homogeneous closed kind of society.

I think it's going to be hard for China to welcome immigrants. [In] my last podcast, I called the immigration into the US our superpower, and if we could just rationalize our policies we could get a steady flow of immigrants, many of whom are skilled and entrepreneurial. It's our superpower basically and I just don't see how China can compete with that.

China Desk

What do you think of the US starting on a course of strategically decoupling its supply chains from China’s? What’s your view of the notion of reciprocity, where what we are not allowed to do in China, they are not allowed to do in America?

David Dollar

I like the concept of a small yard with a high fence, but it is something that's easy to say and hard to actually implement. What goes in the small yard, or how do you keep the yard small?

I think what's helpful from my point of view is to recognize that most of our important partners are more deeply integrated with China than we are.

Countries like Germany, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and some of our southeast asian friends. They're all more deeply integrated with China, so we have to bring them along. I think we have some good recent examples, but if we get out ahead of our partners we're mostly going to be hurting ourselves.

An example would be electric vehicles. The Europeans are welcoming the Chinese and are now ahead in EV technology, and especially batteries. So the Europeans are welcoming Chinese investment into Europe in battery plants and EV assembly. You're going to get integrated European and Chinese production that's very low cost.

We are going to probably end up with very high cost electric vehicle production because we're going to insist on almost all of it being produced in North America. That's not a particularly efficient way of doing things.

I'm a strong defender of national security. I think we need to defend and we need to define the important areas where we want to make sure we're not dependent on anyone who may become an adversary. But I think the danger is we extend it too far if we start defining something as an economic interest.

I think our economic interests are to have the economy grow and for people to be more prosperous. I guess I'm a little worried about the protectionist trend we see in the US, and that we've taken this a little bit too far.

For reciprocity I definitely use that language and it sounds good. But I do think we have to look at each issue carefully.

For example, I think we benefit from having 300,000 Chinese college students in the United States. There's some risks, but I think the benefits outweigh the risks.

Now I'm not sure if there's any specific policy issue that's a problem, but just hypothetically, suppose it were difficult for American students to go study in China. I wouldn't want to change our education policies because of what China's doing. I think we have to kind of use a surgical knife on this rather than a sledgehammer, in figuring out where we want to reciprocate.

China Desk

In this aspect regarding land issues, Americans cannot freely buy land in China so how should we approach that?

David Dollar

Yeah, to be honest I don't have a strong view on that. I mean it's definitely something to worry about.

There are quite a few countries that restrict foreigners' ability to buy agricultural land. I guess I'm open to looking at that. I'm a little bit skeptical. It's really a national security interest.

Recognizing that if we really had a conflict with China, the fact that a farm was owned by the Chinese or some Chinese company that's not going to make any difference. We're just going to expropriate that in a war situation.

I don't see China buying up our agricultural land in a way that threatens our food supply but I understand it's a sensitive issue, and I don't think I'd go to the mat on that one.

China Desk

Where can our readers go to follow your work?

David Dollar

I have a Twitter account, @davidrdollar, the r is important. I host the Brookings trade podcast “Dollar and Sense,” and I have a personal page on the Brookings website www.brookings.edu. You can find me there, and my podcast.